North Leverett Sawmill - 1774

For more than 200 years, this sawmill provided material for houses, barns, churches, bridges, and ships

History of the first mill owners: Captain Joseph Slarrow and Major Richard Montague

It appears that the mill's first two owners, Captain Joseph Slarrow and Major Richard Montague, barely had time to get the mill operating before the American Revolution's call for patriots drove them to recruiting troops and militia for the cause. On trips home from this service, Montague led army recruitment in Leverett. Although descended from the 1660 English Puritan settlement of Hampshire County, he was a devout Baptist dissenter opposed to taxation in support of the organized church. His devout faith apparently did not prevent him from offering strong drink in his Leverett tavern near the Mill on the corner of Cave Hill Road and Hemenway Road.

Montague's entrepreneurial and military partnership with the Leverett newcomer Joseph Slarrow was an unlikely match, for Joseph came from parents who were some of the first non-English immigrants to Massachusetts Bay in 1718. As a Scots Irish (Ulster) outsider, Slarrow's Presbyterian anti-established-church principles were in synch with Montague's, and his resistance to Britain matched that of Leverett's citizens. In 1777 its town meeting voted unanimously "to risque our lives & fortunes in defence of our rights & liberties wherewith God & nature hath made us free.” Slarrow agreed to lead the only militia company to be formed in the town.

With the war, army and navy demands for lumber created an unprecedented market for Leverett timber, an economic opportunity for a town whose extensive forests were its foremost resource. The mill's site near the crossing of three roads combined market access with waterpower and level bottomland for a mill yard. The road access and level field may also have made an ideal site for drilling militia in a town that had no commons, and Major Montague's nearby tavern could have furnished the refreshments troops wanted for their encampments. When Montague bought out Slarrow's interest in 1779, he paid the astonishing sum of 2500 pounds, worth at least $500,000 today.

Leverett's technology and industry had taken root during wartime and established a very valuable industry. In the years to come more than a dozen factories arose around the mill producing scythes and other farm tools, doors and windows, and maple syrup buckets, all needing the lumber. After decades of building Leverett's houses and leading its technological innovation and economic development, this sawmill was still operating 170 years later at the outbreak of World War II. The length of its 45-foot log bed attracted contracts for the extra-long lumber required for the keels and framing timber used in building the U.S. Navy’s all-wooden minesweepers to prevent the ignition of floating magnetic mines.

Researched and written by Will Melton, a public historian studying the Connecticut River Valley and a direct descendant of a member of Joseph Slarrow’s Revolutionary War militia company.

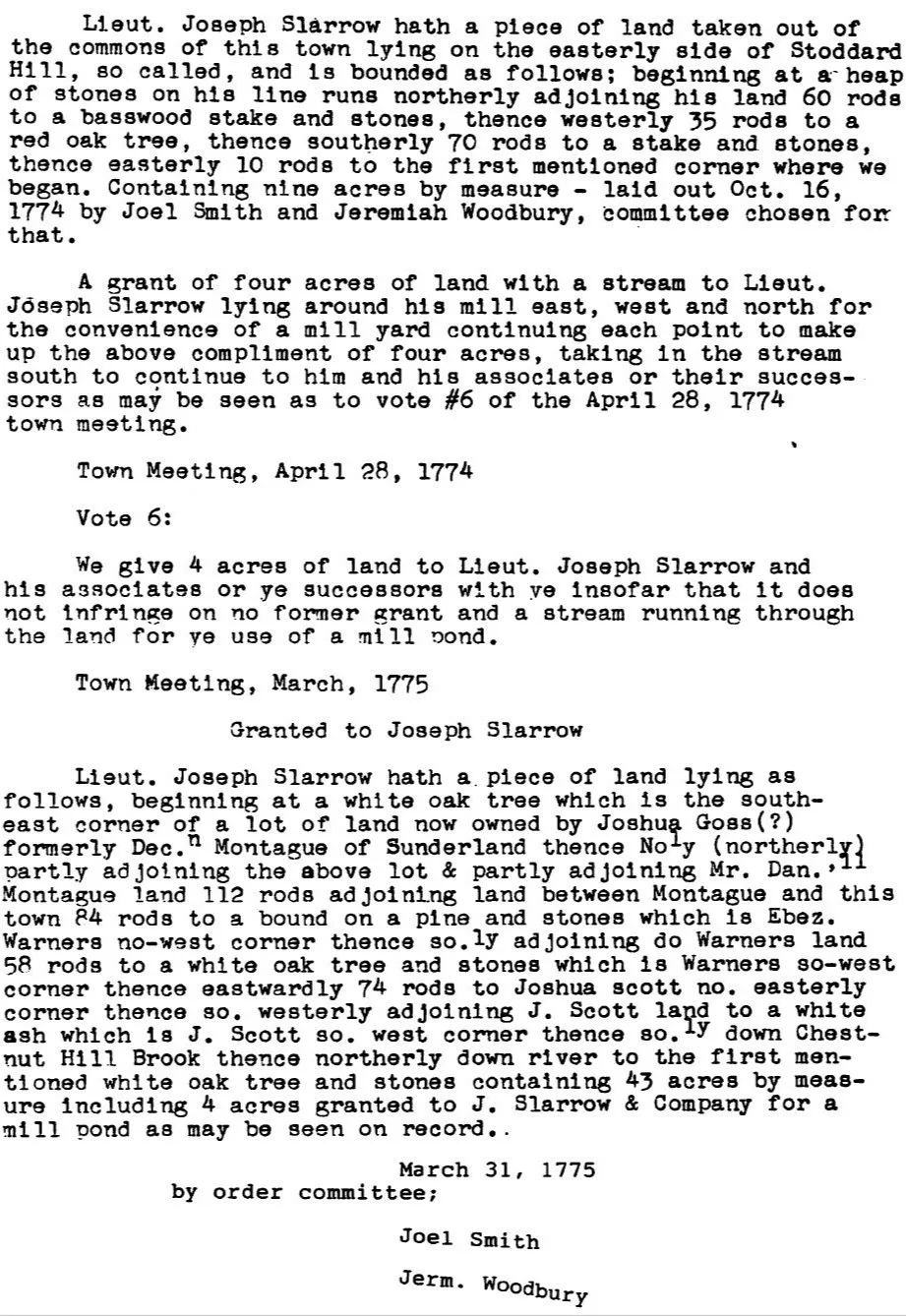

Grant to Joseph Slarrow for the land to build the North Leverett sawmill in 1774. This information was compiled by Wayne Howard and found in the Leverett Historical Society’s archives

The North Leverett Sawmill was able to cut 45-foot long logs to obtain 42-foot timbers during World War II. This letter verifies that ability and was found in the Town archives.

Leverett’s Sawmill River Mills through the Ages

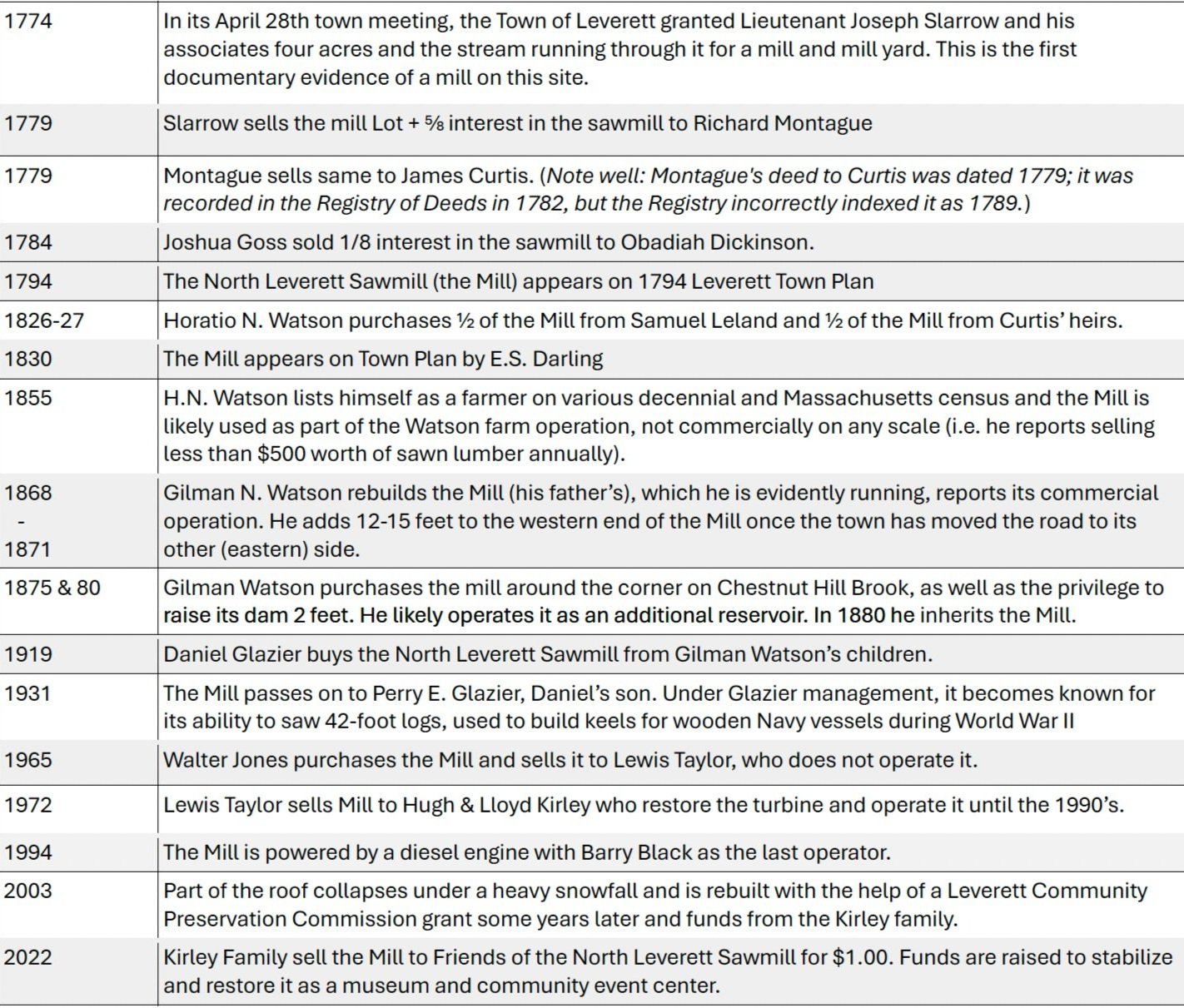

Historic timeline of North Leverett Sawmill ownership. Based on town, county, and national records, including deeds, other documentary evidence, and oral histories, researched and compiled by Pleun Bouricius, Swift River Press Public History and Communications and edited by David Palmer, Leverett.

Original hand drawn map of the mills along North Leverett and Rattlesnake Gutter Roads. This map was made by Annette Gibavic & Clarissa LaClaire of Leverett, housed in the Leverett Historical Commission’s archives in the Town Hall. Eva Gibavic provided a tour of remains of each of these sites and Caldecott-winning author and artist Micha Archer translated it into the fanciful map for Informational Sign #1.

1880 U.S. Census manufacturing schedule of Leverett lumber mills. This snippet from a large United States Census record book is an example of the kind of evidence that helps build the history of the North Leverett Sawmill. The Mill is listed last in both rows. This documentation shows that it was owned by Gilman Watson, operated with two turbines (a modern encased wheel, usually horizontal, and typically made of cast iron or steel until recently), had one circular saw (the large saw) and two other saws, and was operated 12 months of the year, employing two hands. The entry also shows that at that time it was not the largest of six mills in Leverett — which it was to become soon after. This was researched, compiled and written by Pleun Bouricius, Swift River Press Public History and Communications.

This article, written by Nancy Frazier and Pat Reilly, appeared in Yankee Magazine in 1975.

Three years ago, two brothers Lloyd and Hugh Kirley, bought the Sawmill River Lumber Company in North Leverett, Massachusetts, intent upon restoring both its original machinery and purpose. “The first time we saw it, we said, ‘We’ve got to have this place.’ When it did come on the market, we didn’t lose any time haggling,” said Lloyd, the younger of the two red-haired men.

Even though it had stood vacant for seven years, the Mill was in pretty good shape. Still, it took them four days to chip away the rust just to see what the tumblers on the turbine looked like, and a full four months, working from the bottom up, to get the mill going again. Now they operate the only commercial water-powered sawmill in Massachusetts. “Water-power is such a great thing,” said Hugh.

“And they are being careful to keep their only by-product, sawdust, out of the river. Fishing is still good in the mill pond, as are swimming and ice skating.”

Hugh and Lloyd both realize that they cannot compete with modern mills that turn out at least 4000 to 6000 board feet of lumber per day. They can manage 2000 “if things are going well.” Their incentive, rather than industrial, is individual: they love both wood, the strength, the texture, and the essence of the material they are working with.

“We could saw all day. It’s fun.”

“When you see a block 20-by-20 sitting in one piece on the saw, it expands your mind and your thoughts of how you can use wood,” said Hugh.

“I always want to bite into it,” said Lloyd, with a laugh.

“A standard lumberyard will take a beautiful 30’ log and turn it into ‘two-bysies’ (2” x 4” lumber),” lamented Hugh. The Kirleys, on the other hand, are anxious to turn that same log into rough-sawn lumber, even as long as 46’, for the Mill boasts a carriage itself 36’ in length, longer than any around, so far as they know. “Other lumberyards have been sending us their 30 footers,” said Lloyd. “They can’t handle them.”

Apart from its carriage, it can brag of another enviable attribute. Except where it has been repaired, the building is entirely constructed of chestnut. That wood was hand hewn at first, until the structure got up high enough to house the mill machinery. The Kirleys take this as a sign that theirs may have been the first sawmill in the area. They have traced it back as far as 1827 in order to clear water rights, but they know it to be older. It could go back to the 1750s.

As another way of figuring its age, they point out that all of the saw marks carved into the chestnut above the foundations were made by an “up-and-down” saw blade. This predates the circular saw which first came into use around 1814, and which they now use.

Their mill was built to saw beams from big old barns, and since they have the capacity to produce a kind of lumber that is otherwise difficult to come by, they are working out plans for big-timber construction of custom houses, specifically designed to use their product. They see the character of this barn-type-yet-contemporary home as “unfinished.”

“We are after a new system, to use green wood – un-planed, without trim or finish. It has its own feeling,” said Hugh.

Since both men are professionally trained landscape-architects they are sensitive not only to the “feeling” but also to the physical properties of green wood. And it is through their landscaping profession that they hope to support their milling venture.

North Leverett Sawmill Revival

Yankee Magazine photo caption: Hugh Kirley (center) and Lloyd Kirley (right) take a break from work to visit with a friend.

Mill design studio on lower level. The lower level of the mill was used as the design studio for the Kirley’s company Classic Colonial Homes. The business continues in Florence, MA by owner Lance Kirley. Hugh Kirley is shown here with the original mill workings seen along the ceiling.

Historic Preservation

Historic survey of the mill being conducted, circa 2001. Annette Gibavic (right), one of our Town’s historians at that time, with mill owner Hugh Kirley (left) and Lance Kirby (middle), inside the upper level of the mill during a historic assets survey. An application to the National Register of Historic Places was made around that time.

Condition of the mill at that time (2001) when historic survey being done. Photos by Eric Gradoia.

Collapse of the North Leverett Sawmill’s roof in 2003. After the collapse. The roof repair was funded by the citizens of Leverett through a grant from the Leverett Community Preservation Act. Without this repair the mill would have met its end.

Article in the Regional section, Union News, Feb 25, 2003.

The Effect of Old Dams on the Environment

Old mill dams like that of the North Leverett Sawmill are an environmental problem because they silt up the river bottom and prevent riverine species from using the entire river. On the other hand, mill ponds, when no longer used for powering a mill, can be a great resource for flora and fauna as well as for humans. They can be a benefit to the landscape and a unique educational resource. Preserving a mill pond requires, in every single instance, making decisions about which is the greater value. Dams also need to be maintained so they do not turn into a public safety hazard. The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) has an Office of Dam Safety that regulates the permitting process for repairing dams and the Division of Ecological Restoration supports owners who decide to remove their dams. Here is a link to an interesting program that monitors the effect of dams on fish: Connecticut River Shad management Plan.

Researched and written by Pleun Bouricius, Swift River Press Public History and Communications.